Moderator: Moderators

Soft-spoken Lundgren Carries A Very Big Kick

PLAYING THE BAD GUY: Last in a series.

January 13, 1986|JOHN VOLAND

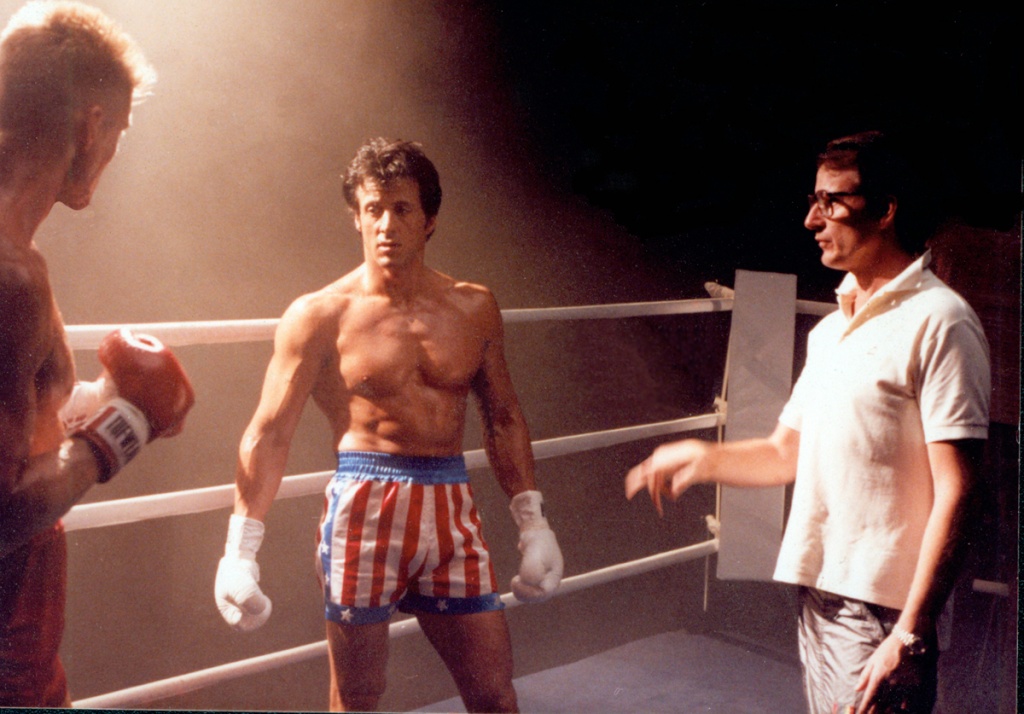

In the climactic scene of the latest "Rocky" installment, Capt. Ivan (Death From Above) Drago, the Soviet Union's Great White Hope, strides confidently through a screaming Moscow crowd to take on the lazy imperialist Rocky Balboa--the representative of the doomed, decadent West.

Mirroring the gigantic poster of him that looms over the arena, there is steel in the young captain's eyes as he throws off his red robe and steps toward the center of the ring. . . .

OK, so it's a bit much . Still, the image that Dolph Lundgren--all 6-foot-6 and 240 pounds of him--renders as Drago is one of patriotic eugenics gone bonkers, a super-boxer who, to quote "Rocky IV's" ad copy, "has an entire country in his corner."

"It's tough enough playing a bad guy when he's only motivated by his own desires," said Lundgren, an affable, even slightly shy Swede of 26. "But when he stands for a whole country, a way of life, that you're supposed to find distasteful . . . well, that's asking quite a bit, I think."

Especially, one might add, when the role is your first national exposure of any substance--and when your background is in kick-boxing and chemical engineering rather than acting.

"Yes, I went through the graduate-school wringer at the University of Sydney (in Australia) and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but the modeling thing took over, especially once I got here," Lundgren recalled. "From there, acting didn't seem like a huge step. So I dropped out of the Ph.D. program at MIT, came down to New York, got an acting teacher and went for it."

Lundgren's classically Aryan features--blond hair, blue eyes, sculpted frame--were a decided plus for Drago (even if he isn't terribly Slavic-looking), but his smile--something he had worked on quite a bit while modeling, he said--was lost on the cutting room floor.

"If I ever smiled during the course of the take, the editor had to go back later and slice it all out," Lundgren said, grinning a bit at the thought. "I was just supposed to glower. Sly (Stallone, who directed the film) kept telling me to be a machine, but I just couldn't help it sometimes."

Indeed, in the finished product, Lundgren-as-Drago not only doesn't smile, he hardly speaks, save to grunt menacingly from time to time. But the former European kick-boxing champ (two years running, in 1981-82) defends that approach to defining this bad-guy boxer.

"I think Drago's really not a bad, bad guy. He's just like another fighter in the ring; all he wants to do is win," Lundgren said, nodding his head for emphasis. "The big difference between Rocky and me is that he's a free agent--or at least has to answer to less malign powers--while Drago is a tool of the state, existing only to exhibit the superiority of the Soviet system. And he's kind of naive; he's really like a lab animal. He is one of those kids who are kept apart and trained like a thoroughbred--he doesn't do anything else."

He paused, wincing slightly, then continued: "But he's not evil; he's just trying to be a winner, and the Soviet system's been very good to him up to this point in his life."

Such a role conception shouldn't leave much room for acting creativity, yet Lundgren said he found a number of ways to take the monolithic quality out of Ivan Drago.

"If you watch Drago after it becomes clear that he is going to lose to Rocky, I tried to put a new awareness in his eyes," Lundgren said, getting up off the vinyl couch to go into a boxing stance. "I kept thinking, 'I'm being used for all this. It doesn't matter to them whether I kill this American, so long as I defeat him,' and there's a kind of hopelessness, a slump of the shoulders, about him after that. He doesn't care to win for an elite that couldn't care less about him--unless he wins."

Audiences certainly care about who wins in this pugilistic summit--to the tune of $100 million in its first five weeks of release--even if, as Lundgren noted, the characters involved are less than realistic.

"Right now we're in the middle of the Commando Era," he remarked with a laugh. "I think it's just one phase, that we'll eventually pass through. And in all these films the bad guys are really bad --with no redeeming social qualities at all. For instance, 'Rambo' was certainly, um, uncluttered with characterization; it was pretty one-dimensional. But it was a huge hit; people loved it. No matter what people say about Stallone, he really gets right through the demographics nonsense--he knows exactly what people want to see, and gives it to them."

And all that audience (and media) attention can't hurt a budding actor's career, can it--especially when that young star happens to have a couple of screenplays he'd like to see financed and produced?

Lundgren laughed and stretched out his long, long legs.

"Nope," he said with a grin. "Couldn't hurt a bit."

Lessons In Aryan Ignorance

January 19, 1986

Having just read the first two columns of John Voland's feature on Dolph Lundgren (Calendar, Jan. 13), I am left in awe of Voland's shameless ignorance and aghast at the obvious absence of any editorial intervention to prevent its display.

Voland writes of "Lundgren's classically Aryan features--blond hair, blue eyes, sculpted frame. . . ." Aryan? "Scandinavian" perhaps. "Nordic," maybe. Even "Viking." But Aryan? I suggest Voland be sent back to school for some basic lessons in history or anthropology or geography.

"Aryan" refers to a language spoken by a people who are supposed to have lived millennia ago on the Iranian Plateau of Southern Asia between the Caspian Sea and the Hindu Kush Mountains.

The World Book Encyclopedia states: "The term Aryan can be used only to describe a language . . . . There is no such thing as an Aryan race."

Webster's New World Dictionary goes a step further: "Aryan has no validity as an ethnological term, although it has been used, notoriously and variously, by the Nazis to mean 'a Caucasian of non-Jewish descent.' " If there were such a thing as an Aryan, he or she would look much more like the Ayatollah Khomaini than Dolph Lundgren.

MICHAEL L. COHEN

West Hollywood

Lady Gaga drew inspiration for her latest effort Born This Way from an unlikely source - Sylvester Stallone's Rocky movies.

The pop star is a big fan of the hit boxing franchise and admits the fighting themes in 1985 movie Rocky IV gave her ideas for her new album.

She tells Rolling Stone magazine, "My favourite part in (Rocky IV) is when Apollo's ex-trainer says to Rocky, 'He is not a machine. He's a man. Cut him, and once he feels his own blood, he will fear you.'

"I know it sounds crazy, but I was thinking about the machine of the music industry. I started to think about how I have to make the music industry bleed to remind it that it's human, it's not a machine."

It's not the first time the Poker Face hitmaker has sung the boxing champ's praises - in a recent U.K. interview with British singer Nicola Roberts, Gaga branded Rocky her "ideal man".

She added, "I never wanted to be the rock star. I wanted to be the girlfriend. I never wanted to be Rocky. I wanted to be (his girlfriend) Adrian."

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 39 guests